Learn about the Maternal and Child Health (MCH) Leadership Competencies by browsing this web page or by downloading the PDF document.

![]() MCH Leadership Competencies, Version 4.5 (PDF - 1 MB)

MCH Leadership Competencies, Version 4.5 (PDF - 1 MB)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

The health of the nation's women, children, youth, and families is influenced by a wide array of factors, including the health practices of individuals and groups, the availability of public health and health care resources, and the social determinants of health (SDOH). At the foundation of a healthy community is a highly qualified, diverse workforce that can positively affect these factors at the individual, community, organizational, and policy levels. Together, this collective is known as the maternal and child health (MCH) workforce.

In 2007, the Health Resources and Services Administration's (HRSA) Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB) first released the MCH Leadership Competencies (Competencies) to support current and future MCH leaders by defining the knowledge and skills necessary to lead in this field. The Competencies, shared across the multiple MCH disciplines, unifies the workforce on a common path to equip the MCH workforce with the knowledge, skills, personal characteristics, and values to improve the health of MCH populations.

From the outset, the Competencies were developed with input from awardees and professional associations. Following a similar process, the Competencies were updated in 2018 in collaboration with those same partners to reflect changes in the leadership skills needed for MCH professionals. In 2023, the Competencies were revised to be more inclusive, appropriate, and reflective of expanding public health practice knowledge.

The Competencies described in this document are drawn from both theory and practice to support and promote leadership across MCH roles and settings. The document is intended to be a resource for MCH interdisciplinary training programs, national, state, and local health agencies, and other MCH organizations to support aspiring and practicing professionals by:

- Defining MCH leadership.

- Describing how the MCH Leadership Competencies can be used by a variety of audiences.

- Providing a conceptual framework for the development of an MCH leader.

- Outlining the knowledge and skill areas required of MCH leaders.

- Linking to tools for implementation.

MCH leaders come from a variety of disciplinary backgrounds (e.g., public health, pediatrics, nutrition, nursing, psychology, social work, family, self-advocacy, education, housing) and build upon their expertise to reach this population through acquisition of MCH-specific knowledge and skills. Therefore, MCH leaders possess core knowledge of MCH populations and their needs. They continually seek new knowledge and improvement of abilities and skills central to effective, self-reflective, and evidence-informed leadership. MCH leaders strive to be attentive, responsive, proactive, empathetic, and respectful in attitudes and working habits. They are also committed to recruiting, training, and mentoring future MCH leaders to ensure the health and well-being of mothers, children, and families - now and in the future. Finally, MCH leaders are responsive to changing community and state, social, scientific, and demographic context and demonstrates the capability to change quickly and adapt in the face of emerging challenges and opportunities.

The MCH Leadership Competencies describe the necessary knowledge, skills (foundational and advanced), and values within a framework designed to support and promote MCH leadership. Therefore, the Competencies can be used in a variety of ways, including:

- As a framework for training objectives for MCH training programs. It is the responsibility of MCH training programs to ensure that graduates have the foundation necessary to work within a variety of professional settings to contribute to the health and well-being of mothers, children, and families - and to inspire others to do likewise.

- To measure and evaluate MCH leadership training. The MCH Leadership Competencies can be used to guide measurement and evaluation of the impact of leadership training.

- To cultivate, sustain, grow, and measure leadership within the current MCH workforce. The MCH Leadership Competencies can be used as a tool to strengthen the leadership abilities of current MCH professionals in national, state, and local health agencies, academia, and other MCH organizations. In particular, the framework can assist in orienting those new to the field to the goals and methods of MCH, assess and promote leadership capacity, and guide continuing education efforts.

Also important is the understanding that leadership (1) can be developed through learning and experience; (2) can be exerted at various levels within an organization and at the national, state, or local levels; and (3) opportunities change over time.

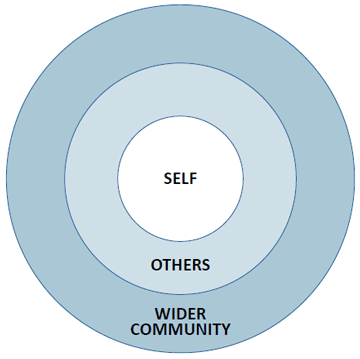

The developmental progression of leadership is of particular importance to those involved in the training and continuing education of MCH health professionals. Leadership ability grows as the knowledge, skills, and experience of the individual expands and deepens. The graphic illustrates the widening spheres of influence that leaders experience as they develop—from self to others to the wider community.

- Self. The leadership process begins with the focus on self where leadership is directed at one's own learning through readings, instruction, reflection, and planned and serendipitous experiences. Individuals increasingly learn to direct their actions and growth toward specific issues, challenges, and attainment of desired goals.

- Others. Leadership in the next sphere extends to coworkers, colleagues, trainees, fellow students, and patients. The behavior and attitudes of others are influenced and possibly altered through the actions and interactions of the individual. Leadership and influence can remain at this level of impact for long periods of time.

- Wider Community. Leadership can also extend to have a broader impact on entire organizations, systems, or general modes of practice. These wider areas of impact and influence require additional skills and a broader understanding of the change process and factors that influence change over time.

The MCH Leadership Competencies are organized within this conceptual framework in a progression from self to wider community demonstrating the widening contacts, broadening interests, and growing influence that MCH leaders can experience over their career. However, despite this organization, the Competencies are applied across the spheres of influence. Each of the 12 Competencies includes a definition and knowledge areas which provide the basis for the foundational and advanced skills.

SELF

- MCH Knowledge Base/Context

- Self-Reflection

- Ethics

- Critical Thinking

OTHERS

- Communication

- Negotiation and Conflict Resolution

- Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility

- Honoring Lived Experience

- Teaching, Coaching, and Mentoring

- Interdisciplinary/Interprofessional Team Building

WIDER COMMUNITY

- Systems Approach

- Policy

As indicated, the MCH Leadership Competencies were first released in 2007. Since that time, they have been refined and modified to reflect changes in the field.

2007 - The MCH Leadership Competencies were developed based on the leadership literature and an iterative (three-year) collaborative process involving input from MCHB grantees, representatives of the Association of Maternal and Child Health Programs (AMCHP), and CityMatCH.

2009 - An updated version of the Competencies was released following a rigorous two-phase Delphi validation process, wherein the initial Competencies were refined to remove redundancies and distill the list based on consensus.

2018 - The MCH Leadership Competencies were revised based on feedback from external partners in the field, a literature review, and input from a workgroup consisting of MCHB grantees, as well as representatives from AMCHP, the Association of University Centers on Disabilities, the Association of Teachers of Maternal and Child Health, and CityMatCH, to reflect changes in the field as well as evolving challenges and priorities.

2023 - The MCH Leadership Competencies were updated to ensure the language is inclusive, appropriate, and reflective of expanding public health practice knowledge. An internal MCHB staff workgroup reviewed each competency, strengthened and revised language, clarified certain knowledge areas and skills, and confirmed consistency throughout. The two main competencies updated were Cultural Competency (now Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility (DEIA), and Family-Professional Partnerships (now Honoring Lived Experience). External partners were invited to review the revised competencies.

This web page provides information about the Competencies including tools for MCH professionals, students, and others working to improve the health and well-being of women, children, and families.

One such tool is the HRSA-funded MCH Navigator managed by the National Center for Education in Maternal and Child Health at Georgetown University. The MCH Navigator includes a self-assessment tool that provides an opportunity to identify learning needs within the MCH

Leadership Competencies and to match those needs with appropriate training. The MCH Navigator provides additional resources for students and practicing professionals learning individually or in groups.

The revised Competencies address the following:

- Expand Cultural Competence to DEIA to better acknowledge systemic discrimination based on factors such as race or ethnicity, religion, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, gender identity, age, abilities, and geographic location as well as how historical trauma impacts MCH.

- Integrate concepts of cultural responsiveness, healthy equity, and social determinants of health (SDOH).

- Encourage the use of plain language in all forms of communication, as suggested by health literacy principles.

- Elevate knowledge generated from lived experience and from communities.

- Expand concepts of Coaching and Mentoring to focus on the mutually beneficial relationships that contribute to building and strengthening the capacity of the public health workforce.

- Enhance the Systems Approach competency to reflect the impact of broader systems on health and well-being of mothers, children, and families.

- Acknowledge the role of clear and equitable organization policies to increase transparency, accountability, and stability.

This document represents the continuation of a dialogue regarding MCH leadership and the MCH Leadership Competencies. As always, we welcome and look forward to your ongoing involvement in examining and defining the knowledge areas and skills that are essential to the practice of effective MCH leadership.

Definition

Maternal and child health (MCH) is a specialty area within the larger field of public health, distinguished by:

- Promotion of the health and well-being of mothers, children, and families. Particular attention is directed to the MCH population domains: women and people who are pregnant or have given birth, infants, children, adolescents, young adults, fathers or other caregivers, and children and youth with special health care needs (CYSHCN.

- A focus on individuals as well as the families, communities, populations, and systems of care in communities that support and are accountable to these individuals.

- A life course perspective as an organizing framework that acknowledges distinct periods in human development and presents both risks and opportunities for interventions to make lasting improvements.

Knowledge Areas

MCH leaders will demonstrate a working knowledge of:

- MCH populations and the history and current structure of the key MCH programs serving these populations, including state Title V programs.

- Core MCH values with a special focus on:

- Prevention

- Individuals and populations

- Life course, including key transitions and intergenerational influences on health

- DEIA

- Partnerships with people with lived experience

- Organizational/interagency partnerships

- Community-based systems of services

- Health equity and elimination of health disparities

- Evidence-informed practice (inclusive of research, contextual, and experiential evidence that can drive decision-making at all levels)

- SDOH

- The services available through major MCH programs and their limitations and gaps.

- The implications of policies, laws, and regulations that may affect MCH populations.

- The underlying principles of public health, population data collection, and analysis as well as the strengths, limitations, and utility of such data.

- The role of federal, state, and local government in ensuring equitable healthcare for women, children, youth, families, and CYSHCN.

- The relationships between public health strategies and clinical strategies to promote health and well-being of mothers, children, and families.

- Understand the use of community generated evidence and how it can complement other forms of evidence.

Skills

Foundational. At a foundational level, MCH leaders will:

- Describe MCH populations and provide examples of MCH programs, including Title V programs.

- Describe the utility of a systems approach in understanding how interactions between individuals, groups, organizations, and communities determine health outcomes.

- Use data to identify issues related to the health status of a particular MCH population group and use these to develop or evaluate policy.

- Describe SDOH, understand health equity, and offer strategies to address health disparities within MCH populations.

- Critically evaluate programs and policies for translation of evidence to practice.

- Understand the value of partnering with people with lived experience and family and community-led organizations to improve programs, policies, and practices.

Advanced. Building on the foundational skills, MCH leaders will:

- Demonstrate the use of a systems approach to examine the interactions among individuals, groups, organizations, and communities.

- Assess the effectiveness of an existing program for specific MCH population groups.

- Ensure that health equity and cultural responsiveness are at the forefront of program planning and service delivery.

Definition

Self-reflection is the process of assessing the impact of values, beliefs, communication, culture, and experiences on one's personal and professional leadership style. By engaging in self-reflection, MCH leaders:

- Develop a deeper understanding of their personal and cultural biases, experiences, values, and beliefs, and how these may influence future action and learning.

- Identify personal strengths in both informal and organizational contexts.

- Explore personal leadership styles and attributes, and how those are valued in current and potential work settings.

- Establish and maintain professional boundaries in ways that prioritize their physical, mental, and emotional health.

Knowledge Areas

MCH leaders will demonstrate a working knowledge of:

- The impact of self-assessment and self-reflection on leadership style, interpersonal interactions, and cultural responsiveness.

- Characteristics and use of different leadership styles.

- Sources of personal fulfillment, resilience, and rejuvenation, as well as signs of stress and fatigue.

Skills

Foundational. At a foundational level, MCH leaders will:

- Recognize how one's personal values, beliefs, communication, culture, and experiences influence one's leadership practice.

Advanced. Building on the foundational skills, MCH leaders will:

- Use self-reflection techniques to strengthen communication across program development and implementation, service delivery, clinical care, community collaboration, teaching, research, and scholarship.

- Seek and use feedback from peers and mentors to improve leadership practice.

- Apply understanding of one's own leadership style and sources of personal resilience to assemble and promote cohesive, well-functioning teams with diverse perspectives and complementary styles.

Definition

Maternal and child health (MCH) is a specialty area within the larger field of public health, distinguished by:

- Promotion of the health and well-being of mothers, children, and families. Particular attention is directed to the MCH population domains: women and people who are pregnant or have given birth, infants, children, adolescents, young adults, fathers or other caregivers, and children and youth with special health care needs (CYSHCN.

- A focus on individuals as well as the families, communities, populations, and systems of care in communities that support and are accountable to these individuals.

- A life course perspective as an organizing framework that acknowledges distinct periods in human development and presents both risks and opportunities for interventions to make lasting improvements.

Knowledge Areas

MCH leaders will demonstrate a working knowledge of:

- MCH populations and the history and current structure of the key MCH programs serving these populations, including state Title V programs.

- Core MCH values with a special focus on:

- Prevention

- Individuals and populations

- Life course, including key transitions and intergenerational influences on health

- DEIA

- Partnerships with people with lived experience

- Organizational/interagency partnerships

- Community-based systems of services

- Health equity and elimination of health disparities

- Evidence-informed practice (inclusive of research, contextual, and experiential evidence that can drive decision-making at all levels)

- SDOH

- The services available through major MCH programs and their limitations and gaps.

- The implications of policies, laws, and regulations that may affect MCH populations.

- The underlying principles of public health, population data collection, and analysis as well as the strengths, limitations, and utility of such data.

- The role of federal, state, and local government in ensuring equitable healthcare for women, children, youth, families, and CYSHCN.

- The relationships between public health strategies and clinical strategies to promote health and well-being of mothers, children, and families.

- Understand the use of community generated evidence and how it can complement other forms of evidence.

Skills

Foundational. At a foundational level, MCH leaders will:

- Describe MCH populations and provide examples of MCH programs, including Title V programs.

- Describe the utility of a systems approach in understanding how interactions between individuals, groups, organizations, and communities determine health outcomes.

- Use data to identify issues related to the health status of a particular MCH population group and use these to develop or evaluate policy.

- Describe SDOH, understand health equity, and offer strategies to address health disparities within MCH populations.

- Critically evaluate programs and policies for translation of evidence to practice.

- Understand the value of partnering with people with lived experience and family and community-led organizations to improve programs, policies, and practices.

Advanced. Building on the foundational skills, MCH leaders will:

- Demonstrate the use of a systems approach to examine the interactions among individuals, groups, organizations, and communities.

- Assess the effectiveness of an existing program for specific MCH population groups.

- Ensure that health equity and cultural responsiveness are at the forefront of program planning and service delivery.

Definition

Complex challenges faced by MCH populations and the systems that serve them require critical thinking. Critical thinking is the ability to identify an issue or problem, frame it as a specific question, consider it from multiple perspectives, evaluate relevant information, and develop a resolution.

Evidence-informed decision-making is the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence to guide practice, policy, and research. It is an advanced manifestation of critical thinking skills.

Implementation science is also a vital component of critical thinking to promote the timely adoption and integration of evidence-informed practices, interventions, and policies.

Knowledge Areas

MCH leaders will demonstrate a working knowledge of:

- The components of critical thinking: knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation.

- Basic statistics, epidemiology, qualitative and quantitative research, systematic review, and meta-analysis.

- The types of evidence used in guidelines and recommendations for public health and clinical practice, including lived experience and community-generated knowledge.

Skills

Foundational. At a foundational level, MCH leaders will:

- Evaluate various perspectives, sources of information, strengths and limitations of various approaches, and possible unintended consequences of addressing a clinical, organizational, community-based, or research challenge.

- Use population data, community input, and lived experience to determine the needs of a population for the purposes of designing programs, formulating policy, and conducting research or training.

- Demonstrate the ability to use an equity lens to critically analyze research, programs, and policies.

Advanced. Building on the foundational skills, MCH leaders will:

- Present and discuss a rationale for policies and programs that is grounded in evidence and addresses the information needs of diverse audiences.

- Use implementation science to analyze and translate evidence into policies and programs.

- Identify and propose promising practices and policies that can be used in situations where action is needed, but where the evidence base is not yet established.

- Develop and apply evidence-informed practice guidelines and policies in their field.

Definition

Communication is the verbal, nonverbal, and written sharing of information. The communication process consists of a sender who develops and presents the message and the receiver who works to understand the message. Communication involves both the message and how the message is presented. Health communication is vital for influencing behavior that can lead to improved health.

Skillful communication is the ability to convey information to and receive information from others effectively. It includes essential components of attentive listening and clarity in writing for or presenting to (through speaking, signing, use of augmentative and alternative communication devices, etc.) a variety of audiences. An understanding of the impact of culture, language, literacy level, and disability on communication between MCH professionals and the individuals, families, and populations they serve is also important.

Knowledge Areas

MCH leaders will demonstrate a working knowledge of:

- Principles of communication using different modalities, including verbal, written, and nonverbal, in various practice, policy, and research settings.

- Approaches to address differences in communication needs, such as literacy levels, disability, technical jargon, and acronyms.

- Cultural responsiveness in communicating with individuals and communities.

- The role of health literacy in ensuring equitable access to information and services.

Skills

Foundational. At a foundational level, MCH leaders will:

- Share thoughts, ideas, and feelings effectively with individuals and groups from diverse backgrounds.

- Communicate clearly and effectively using plain language and other accessibility principles to express information about issues that affect MCH populations.

- Cultivate active listening skills and attentiveness to nonverbal communication cues.

- Tailor information for the intended audience(s), purpose, and context by using appropriate communication messaging, tools like interpretation services, and health literacy principles, and using different modalities for dissemination. Audiences can include consumers, policymakers, clinicians, and the public.

Advanced. Building on the foundational skills, MCH leaders will:

- Employ foundational communication skills in challenging situations, such as receiving or presenting information during an emergency, relaying difficult news, or explaining opportunities and risks for health promotion and disease prevention.

- Summarize complex information appropriately for a variety of audiences and contexts.

Definition

Negotiation is a cooperative process where participants try to find a solution that meets the legitimate interests of involved parties.

Conflict resolution is the process of resolving or managing a dispute by sharing each party's perspective and adequately addressing their interests so that they are satisfied with the outcome.

Leadership in MCH requires knowledge and skills in negotiation and conflict resolution to address differences among groups.

MCH professionals approach conflict and negotiations with knowledge of interpersonal and systemic power differentials, and awareness of their own perspectives and implicit biases. They acknowledge that relationship building and development of trust are critical long-term outcomes. They recognize when compromise is appropriate to overcome an impasse and when persistence toward a different solution is warranted.

Knowledge Areas

MCH leaders will demonstrate a working knowledge of:

- Characteristics of conflict and how conflict manifests in organizational contexts.

- Sources of potential conflict in interdisciplinary, community, and family settings. These could include differences in terminology and norms among disciplines, the dynamics between communities and institutions, and the relationships between individuals.

- Approaches to conflict management and negotiation.

- Strategies and techniques useful for successful negotiation with groups with diverse backgrounds, strengths, and resources.

- How conflict can be a catalyst for positive change.

Skills

Foundational. At a foundational level, MCH leaders will:

- Understand their own implicit biases, points of view, and styles of managing conflict and negotiation; and possess emotional self-awareness and self-regulation.

- Understand others' points of view, how various styles can influence negotiation and conflict resolution, and how to adapt to others' styles to navigate differences.

- Apply strategies and techniques of effective negotiation and evaluate the impact of communication and negotiation styles on outcomes.

Advanced. Building on the foundational skills, MCH leaders will:

- Demonstrate the ability to manage conflict in a constructive manner.

- Navigate and address the ways identity, culture, power, socioeconomic status, and inequities shape conflict and the ability to come to resolution.

- Use consensus building to achieve mutual understanding of challenges and opportunities, establish common goals, and agree on approaches for solving problems.

Adapted from NIH Fogarty International Center Implementation Science Information and Resources. Implementation science news, resources and funding for global health researchers.

Adapted from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Inclusive Communications Principles: Using a Health Equity Lens. Available at Using a Health Equity Lens | Gateway to Health Communication | CDC.

Definition

DEIA are linked approaches to create communities and spaces that respect all people and work toward achieving optimal outcomes. It broadly represents knowledge and skills necessary to interact effectively and increase belonging. Leading with DEIA ensures that the needs of all people and communities are met in a respectful and responsive way that eliminates barriers to equity and full participation in society, decreases disparities, and improves health outcomes.

Health equity means that all people, including mothers, fathers, birthing people, children, and families achieve their full health potential. Achieving health equity is an active and ongoing process that requires commitment at the individual and organizational levels, and within communities and systems. Achieving health equity requires eliminating inequities, including poverty, racism, ableism, gender discrimination, and other historical injustices.

- Diversity is the practice of including the many communities, identities, races, ethnicities, backgrounds, abilities, cultures, and beliefs of all people, including historically marginalized and underserved and under-resourced communities.

- Equity is the consistent and systemic fair, just, and impartial treatment of all individuals, including individuals who belong to historically marginalized and underserved communities that have been denied such treatment.

- Inclusion means the acceptance and encouragement of the presence and participation of a diversity of people in social, educational, work, and community settings.

- Accessibility is the design, construction, development, and maintenance of facilities, information and communication technology, programs, and services so that all people, including people with disabilities, can fully and independently use them.

Cultural responsiveness is one practice to advance DEIA by understanding and respecting culture - including actions, beliefs, customs, institutions, language, and literacy (including health literacy and language proficiency), thoughts, and values held by groups while recognizing that individuals are often part of more than one cultural group. It includes being aware of one's own and other's group memberships and histories; considering how past and current circumstances contribute to presenting behaviors; examining one's own attitudes and biases and seeing how they impact relationships; articulating positive and constructive views of difference; and making tangible efforts to reach out and understand differences.

MCH professionals integrate DEIA through interpersonal interactions and through the design of interventions, programs, and research studies that recognize, respect, and support differences. MCH leaders should be able to apply strategies from evidence-informed training on reducing implicit bias and enhancing cultural responsiveness.

Knowledge Areas

MCH leaders will demonstrate a working knowledge of:

- How conscious and unconscious biases and assumptions influence individuals and organizations.

- How policies, structural legacies, and the experiences of historical trauma and of systemic discrimination intersect and impact health outcomes for MCH populations.

- How multiple SDOH create disparities that influence health and access to health care services, including how the intersectionality of SDOH can work together to impact equity.

- How using DEIA principles can increase access, engagement, and belonging in research, programs, the workplace, and other systems.

Skills

Foundational. At a foundational level, MCH leaders will:

- Conduct personal and/or organizational self-assessments regarding DEIA.

- Identify and elevate the strengths of individuals and communities based on sensitivity and respect for their diverse backgrounds and lived experiences and respond appropriately.

- Incorporate an understanding and appreciation of differences in experiences and perspectives into professional behaviors and attitudes while maintaining an awareness of the potential for implicit bias.

Advanced. Building on the foundational skills, MCH leaders will:

- Modify clinical and public health systems to meet the specific needs of a group, family, community, or population.

- Employ strategies to ensure equitable public health and health service delivery systems.

- Integrate DEIA into programs, research, scholarship, communications, and policies.

- Use data-driven tools and data disaggregation to guide efforts toward health equity and use plain language to present data.

Vohra-Gupta, S, Petruzzi, L, et al. An Intersectional Approach to Understanding Barriers to Healthcare for Women. Journal of Community Health 48, 89-98 (2023)

Definition

Honoring lived experience ensures the health and wellbeing of MCH populations through respectful collaboration and shared decision making. Additionally, partnerships with organizations led by people with lived experience honor the strengths, culture, traditions, and expertise that everyone brings to the relationship when engaged in program planning, implementation, evaluation, and policy activities. These partnerships can also help MCH leaders connect with people with lived experience from diverse backgrounds to ensure the perspectives of the communities who receive services are represented.

Historically in the field of MCH, the concept of family-centered care was developed within the community of parents, advocates, and health professionals working with CYSHCN, with the goal that all care is received in family-centered, comprehensive, coordinated systems. CYSHCN have or are at increased risk for chronic physical, developmental, behavioral, or emotional conditions. They also require health and related services of a type or amount beyond that required by children generally. The field now recognizes that self-advocates also provide critical insights and perspectives to the successful development of effective policies, practices, and care delivery.

Self-advocates are individuals being served by MCH programs who have personal experience in a system of care and have the self-determination to communicate their own interests, desires, needs and rights.

Family perspectives and individual, self-advocate expertise constitute two distinct, valued perspectives that each provide unique knowledge to the field. Family members, self-advocates, and others with lived experience can serve as faculty, staff, and consultants to provide interdisciplinary teams with their perspective of receiving care and services. People with lived experience as leaders and teachers are invaluable to training programs, clinical services, and other public health programs.

The key to effective partnerships with people with lived experience entails:

- Shared decision making, involving self-advocates and/or the family, in planning and implementing activities.

- Addressing the priorities of people with lived experience using a strengths-based approach.

- Recognizing the agency of self-advocates in decision-making as they approach transition age, and across the lifespan.

- Connecting people with lived experience to needed services.

- Acknowledging that the effects of the SDOH, and broader systems of care, greatly impact individuals with special health care needs and developmental disabilities.

Knowledge Areas

MCH leaders will demonstrate a working knowledge of:

- The expertise of people with lived experience in developing programs and services.

- The person-centered care perspective at the individual, organizational, and systems level in MCH policies, programs, or practice.

- The family-centered care perspective at the individual, organizational, and systems level in MCH policies, programs, or practice.

Skills

Foundational. At the foundational level, MCH leaders will:

- Solicit and implement input from people with lived experience in the design and delivery of clinical or public health services, program planning, materials development, program activities, and evaluation. Also, compensate participants as appropriate for such services.

- Provide training, mentoring, and other opportunities to people with lived experience, and community members, to lead advisory committees or task forces. Furthermore, seek training and guidance from these groups to inform program and care development.

- Demonstrate shared decision-making among individuals, families, and professionals using a strengths-based approach to strengthen practices, programs, or policies that affect MCH populations.

- Assess and tailor recommendations to social, educational, and cultural issues affecting people with lived experience.

- Celebrate individual and family diversity and provide an open and accepting environment.

Recognize that organizational and system-level policies and practices may impact people with lived experience as well as acknowledge the role that people with lived experience can play in influencing policy and practice.

Advanced. Building on the foundational skills, MCH leaders will:

- Collaborate with organizations that are led by people with lived experience to build and deepen involvement across all MCH programs.

- Use feedback from people with lived experience, and community members, obtained through focus groups, surveys, community advisory boards, and other mechanisms as part of the project's continuous quality improvement efforts. Monitor and assess the program overall for effectiveness of partnerships between professionals and people with lived experience.

- Ensure that perspectives from people with lived experience are actively informing the development, implementation, and critical evaluation of MCH research, clinical practice, programs, and policies.

- Assist health care professionals, organizations, and health plans to develop, implement, and evaluate models of family-professional partnerships and direct partnerships with self-advocates.

- Incorporate content about partnerships between people with lived experience and professionals into health professions and continuing education curricula and assess the impact of this training on professional skills, programs, and policies.

Definition

Teaching, coaching, and mentoring are three primary strategies used to develop others. The relationships between teachers and students, coaches and coaching participants, and mentors and mentees are mutually beneficial relationships that contribute to building and strengthening the capacity of the public health workforce.

Teaching involves designing a learning environment, which can include developing objectives and curricula; providing resources and training opportunities; modeling the process of effective learning; and evaluating whether learning occurred.

Coaching refers to methods of training, counselling, or instructing an individual or group how to maximize their potential by developing skills, examining their assumptions, setting goals, taking appropriate actions, and reflecting on the outcomes.

Mentoring is a reciprocal learning relationship in which a mentor and mentee work collaboratively toward the achievement of mutually defined goals that will develop participants' skills, abilities, knowledge, and/or thinking.

Knowledge Areas

MCH leaders will demonstrate a working knowledge of:

- A variety of teaching strategies and tools that are inclusive of different learning styles, culturally responsive, and appropriate to the goals and needs of diverse learners.

- Coaching as a professional relationship that offers tools for dealing with and leading change, working with others, and navigating conflict.

- Mentoring as a personal, career-oriented relationship to promote the mentees' professional growth, enhance their skill sets, and increase their knowledge of relevant resources.

- Teaching, coaching, and mentoring as a tool for leadership development and succession planning.

Skills

Foundational. At the foundational level, MCH leaders will:

- Practice humility and cultivate rapport so that teaching, mentoring, and coaching relationships can be productive.

- Clearly set and continuously reinforce boundaries and define expectations in a mentoring or coaching relationship.

- Use instructional technology tools that facilitate broad participation based on DEIA principles.

- Give and receive constructive feedback about behaviors and performance.

- Cultivate active listening skills.

Advanced. Building on the foundational skills, MCH leaders will:

- Incorporate inclusive evidence-informed education and be responsive to individuals' needs for accommodations.

- Consistently engage individuals using active learning methods.

- Effectively facilitate learning in groups with individuals of varying baseline knowledge, skills, and experiences.

- Expand beyond task- or project-focused coaching to career- and professional advancement-focused coaching and mentoring.

- Contribute to diversity in leadership by facilitating equitable, culturally appropriate, and accessible opportunities for teaching, coaching, and mentoring.

Adapted from Dopson SA, et al. Structured Mentoring for Workforce Engagement and Professional Development in Public Health Settings.

Definition

MCH systems are interdisciplinary/interprofessional (ID/IP) in nature. ID/IP practice provides a supportive environment in which team members from different disciplines and sectors, are acknowledged and seen as essential and synergistic. Input from each team member is elicited and valued in making collaborative, outcome-driven decisions to address individual, community-level, or systems-level problems. The “team”, which is the core of ID/IP practice, is characterized by shared leadership, equal or complementary investment in the process, and accountability for outcomes.

Knowledge Areas

MCH leaders will demonstrate a working knowledge of:

- The role of ID/IP teams in building stronger outcomes.

- Team building concepts, including stages of team development; practices that enhance teamwork; and management of team dynamics.

Skills

Foundational. At the foundational level, MCH leaders will:

- Accurately describe roles, responsibilities, and scope of practice of all members of the ID/IP team.

- Actively seek out and use input from people with diverse perspectives in decision making processes.

- Identify and assemble team members with knowledge and skills appropriate to a given task.

- Facilitate group processes for team-based decisions, including articulating a shared vision, building trust and respect, and fostering collaboration and cooperation.

Advanced. Building on the foundational skills, MCH leaders will:

- Identify and redirect forces that negatively influence team dynamics.

- Use a shared vision of mutually beneficial outcomes to promote team synergy.

- Share leadership based on appropriate use of team member strengths in carrying out activities and managing challenges.

- Adopt tools, techniques, and methods from a range of disciplinary knowledge and practice bases to address challenges and meet needs.

- Use knowledge of competencies and roles for disciplines other than one's own to improve teaching, research, advocacy, and systems of care.

Definition

Improving the health and well-being of mothers, children, and families is a complex process because these populations are influenced by many intersecting factors. Systems thinking recognizes this complexity and examines the linkages between components - norms, laws, resources, infrastructure, and individual behaviors - that affect outcomes. Systems thinking addresses how these components interact at multiple levels and the leadership required to make advances within and across those levels.

MCH leaders will demonstrate a working knowledge of:

- How organizations or practice settings function as systems, including business and administrative principles related to planning, funding, budgeting, staffing, and evaluation.

- How organizations or practice settings function in relation to broader systems, including principles of systems thinking; features and issues of systems (including but not limited to health economics and health policy); principles of building constituencies and engaging in collaborative endeavors; and concepts of implementation science and factors that influence use of research findings in practice.

Skills

Foundational. At the foundational level, MCH leaders will:

- Ensure the mission, vision, and goals of an organization relate to the broader system in which it belongs and advance DEIA to facilitate shared understanding, responsibility, and action.

- Practice budgeting, effective resource use, continuous quality improvement, coordination of tasks, and problem solving.

- Develop projects that reflect a broader systems approach and lead meetings/teams effectively.

- Identify external partners and the extent of their engagement in the collaborative process.

- Interpret situations using a systems perspective (i.e., identify both the whole system and the dynamic interplay among its parts).

- Assess the environment, with community, family, and individual input, to determine goals and objectives for a new or continuing program, list factors that facilitate or impede implementation of evidence-informed/informed strategies, develop priorities, and establish a timeline for implementation.

Advanced. Building on the foundational skills, MCH leaders will:

- Manage a project effectively and efficiently, including planning, implementing, delegating, sharing responsibility, staffing, and evaluating.

- Use implementation science to promote use of evidence-informed practices.

- Develop proficiency in program administration, policy development, and health care financing.

- Acknowledge the impact of historical oppression that has led to disparities in MCH populations to maintain and grow strong external partnerships based on openness, inclusion, and trust.

- Build effective and sustainable coalitions to achieve equitable, population outcomes.

- Use community collaboration models (e.g., collective impact) and leverage existing community improvement efforts to define a meaningful role for MCH.

Definition

It is important for MCH leaders to possess policy skills, particularly in changing state and community environments. MCH leaders understand the resources necessary to improve health and well-being of mothers, children, and families, and the need to be able to articulate those needs in the context of policy development and implementation at all levels.

A public policy is a law, regulation, procedure, administrative action, or voluntary practice of government that affects groups or populations and influences resource allocation.

Organizations also create policies to provide guidelines for decision making processes. Clear and equitable policies contribute to increased transparency, accountability, and stability. They have both a direct and indirect impact on the MCH workforce and populations.

Knowledge Areas

MCH leaders will demonstrate a working knowledge of:

- Government policy-making processes at the local, state/jurisdiction, and national levels.

- Current public policies and private-sector initiatives that are especially relevant to MCH populations.

- Appropriate methods for informing and educating policymakers about the diverse needs of MCH populations and the impact of current policies on those populations.

- Strategies for organizational and public-facing communications regarding key MCH priorities.

Skills

Foundational. At the foundational level, MCH leaders will:

- Frame problems based on key data that affect MCH populations, including epidemiological, economic, and other community and state/jurisdictional trends.

- Use available sources of evidence when assessing the effectiveness of existing policies or proposing policy change.

Distinguish the roles and relationships of groups (executive, legislative, and judicial branches, as well as interest groups and community coalitions) involved in the public policy development and implementation process.

Advanced. Building on the foundational skills, MCH leaders will:

- Apply appropriate evaluation standards and criteria to the analysis of alternative policies.

- Analyze the potential impact of policies using an equity lens on MCH populations.

- Formulate strategies to balance the interests of diverse partners in ways that are consistent with MCH priorities.

Effectively present evidence and information as a cohesively crafted MCH story to a legislative body, key decision makers, foundations, or the general public to inspire action.

8 Adapted from Adapted from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Inclusive Communications Principles: Using a Health Equity Lens. Using a Health Equity Lens | Gateway to Health Communication | CDC

This publication was produced by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), HRSA, MCHB under contract number 75R60219D00039/75R60220F34001.

This publication lists non-federal resources to provide additional information to consumers. The views and content in these resources have not been formally approved by HHS or HRSA. Listing these resources is not an endorsement by HHS or HRSA.

Maternal and Child Health Leadership Competencies is not copyrighted. Readers are free to duplicate and use all or part of the information contained in this publication; however, the photographs are copyrighted and may not be used without permission.

Pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 1320b-10, this publication may not be reproduced, reprinted, or redistributed for a fee without specific written authorization from HHS.

Stock photography credits:

Cover - iStock.com/FatCamera

Page 6 - GettyImages.com/VioletaStoimenova

Page 14 - GettyImages.com/Akarawut Lohacharoenvanich

Page 18 - GettyImages.com/Jupiterimages

Page 28 - GettyImages.com/ monkeybusinessimages

Suggested citation: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Maternal and Child Health Leadership Competencies. Rockville, Maryland: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, June 2023.

Kaitlin Bagley, MPH

Division of MCH Workforce Development, Maternal and Child Health Bureau

Julia Fantacone, MPP, PMP

Altarum Institute

Laurel Huffman, MPH, CPH, RDN, LDN

Division of MCH Workforce Development, Maternal and Child Health Bureau

Ayanna Johnson, MSPH

Division of MCH Workforce Development, Maternal and Child Health Bureau

Meredith Morrissette, MPH

Division of MCH Workforce Development, Maternal and Child Health Bureau

Lauren Raskin Ramos, MPH

Division of MCH Workforce Development, Maternal and Child Health Bureau

Jennifer Rogers, MPH

Altarum Institute

Robyn Schulhof, MA

Division of MCH Workforce Development, Maternal and Child Health Bureau

Caley Small, MPH

Altarum Institute

Major recommendations addressed in the revised Competencies, by sphere of influence, are:

Self

- Highlight the importance of assembling and promoting a cohesive, well-functioning team with diverse and complementary styles.

- Elevate cultural competence as an MCH leadership ethic.

Others

- Address the ways culture, power, and inequities shape conflict and the ability to come to resolution.

- Recognize and address cultural differences from a broad range of experiences and perspectives.

Wider Community

- Include coaching as an important skill for leaders. Coaching is distinct from mentoring and teaching.

- Add the term “interprofessional” to all mentions of “interdisciplinary” indicating a broader understanding of the variety of professionals, MCH populations, family and self-advocate leaders, and community partners included in such teams.

- Focus on systems thinking and implementation science to address complex issues affecting MCH populations.

MCHB's Division of MCH Workforce Development would like to thank the following people for their helpful comments, edits, and assistance at various stages of updating the MCH Leadership Competencies:

Kruti Archarya, MD, FAAP

University of Illinois Chicago

Nikeea Copeland Linder, PhD, MPH

Kennedy Krieger Institute

Jackie Czyzia, MPH

Association of University Centers on Disabilities

Ben Kaufman, MSW

Association of Maternal and Child Health Programs

Shokufeh M. Ramirez, PhD, MPH

Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine

John Richards, MA, AITP

National Center for Education in Maternal and Child Health

Jennifer Rogers, MPH

Altarum Institute

Dawn Rudolph, MSEd

Association of University Centers on Disabilities

Candice Simon, MPH

Association of Maternal and Child Health Programs

Caley Small, MPH

Altarum Institute

Marsha Lynn Spence, PhD, MPH, RDN, LDN

University of Tennessee Knoxville